Michael Whelan

behaviour driven blog

Porting a .Net Framework Library to .Net Core

I have recently been involved with porting a couple of open source frameworks to .Net Core. It's a brave new world, with lots of new things to discover and learn. In this post I am going to outline the process I've followed to convert my code and a few of the things I've learned along the way. Hopefully, this post will shed some light on the process if you are looking to port your .Net Framework code to .Net Core. Special thanks to Jake Ginnivan who, as always, was a font of knowledge on all things programming during the porting exercises!

Run the .Net Portability Analyzer

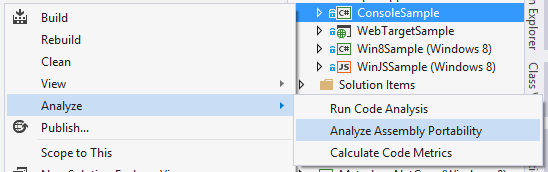

Before you even attempt to port your library, you should run the .Net Portability Analyzer on your existing project. This is available as a console application or a Visual Studio plugin. You can access the Visual Studio plugin by right clicking on the project and selecting Analyze -> Analyze Assembly Portability.

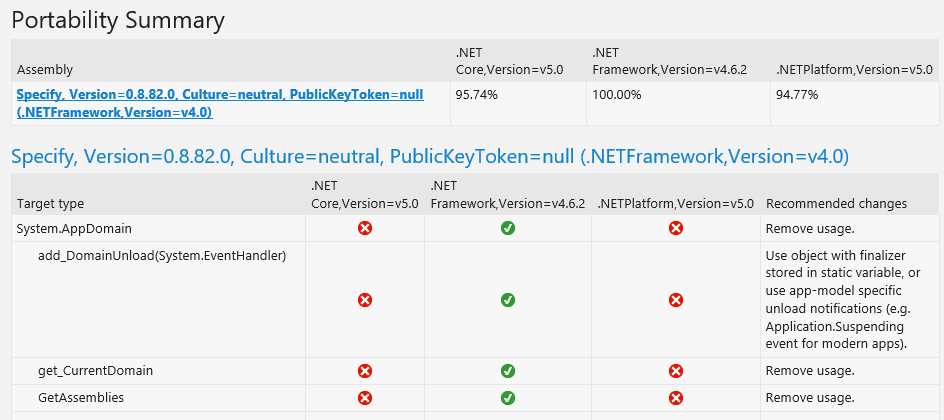

This will produce a report that provides two useful pieces of information:

- High-level summary: The summary gives you a percentage for each of your assemblies, telling you how much of your framework usage is portable to .NET Core.

- List of non-portable APIs: It provides a table that lists all the usages of APIs that aren’t portable. Most usefully, it also includes a list of recommended changes.

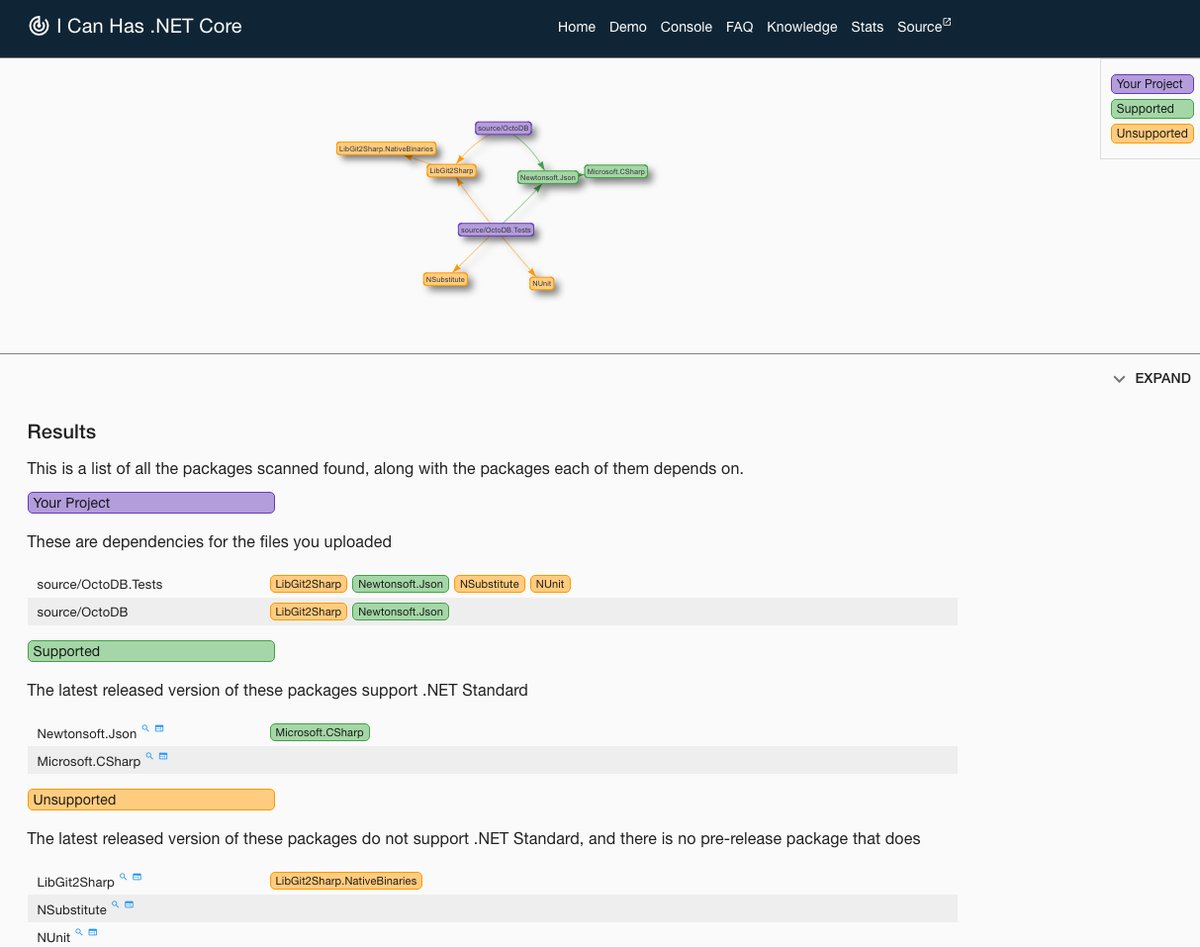

Run I Can Has .Net Core

Another useful analysis tool is the I Can Has .Net Core website. Just upload your project's packages.config, project.json or paket.dependencies files for analysis and it will build a visualisation of the packages and whether .NET Standard versions are available on nuget.org.

Create a new .Net Core class library project

The way to "upgrade" a .Net framework project is actually to create a new .Net Core class library and copy the old C# files into it. Assuming you want it to have the same name as the old project, and be in the same folder, you should remove the existing project and rename its folder on the file system so that the new project can be saved to the original location.

Add a global.json file

You will need to add a global.json file to the solution, which is used to configure the solution as a whole. It includes just two sections, projects and sdk by default.

{

"projects": [ "app", "tests" ],

"sdk": { "version": "1.0.0-preview2-003121" }

}

The projects property designates which folders contain source code for the solution. The sdk property specifies the version of the DNX (.Net Execution Environment) that Visual Studio will use when opening the solution. (I think DNX might no longer be the correct terminology. .Net Core has been an ever moving target).

Add target frameworks to project.json file

The frameworks node in project.json specifies the framework versions that the project should be compiled against. In this example, the library will support .Net 4 (net40) and .Net Standard 1.5 (netstandard1.5). Because .Net Core has been decomposed into many modules, this allows you to specify the additional NuGet package dependencies that .Net Core needs (shown in the netstandard1.5 node below).

{

"version": "1.0.0-*",

"dependencies": {

"LibLog": "4.2.5",

"TestStack.BDDfy": "4.3.0"

},

"frameworks": {

"net40": {

"dependencies": {

},

"frameworkAssemblies": {

"System.Runtime.Serialization": "4.0.0.0",

"System.Xml": "4.0.0.0"

}

},

"netstandard1.5": {

"imports": "dnxcore50",

"buildOptions": {

"define": [

"LIBLOG_PORTABLE",

"NETSTANDARD1_5"

]

},

"dependencies": {

"NETStandard.Library": "1.6.0",

"Microsoft.CSharp": "4.0.1",

"System.Dynamic.Runtime": "4.0.11"

}

}

}

}

Fixing missing references for .Net Core

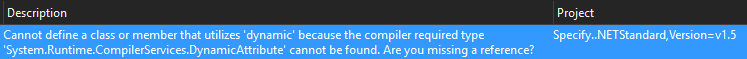

When you first build the project, you will most likely get a lot of missing reference exceptions for the .Net Standard target framework (see image below). Note that the project is specified as [ProjectName].NetStandard, Version 1.5.

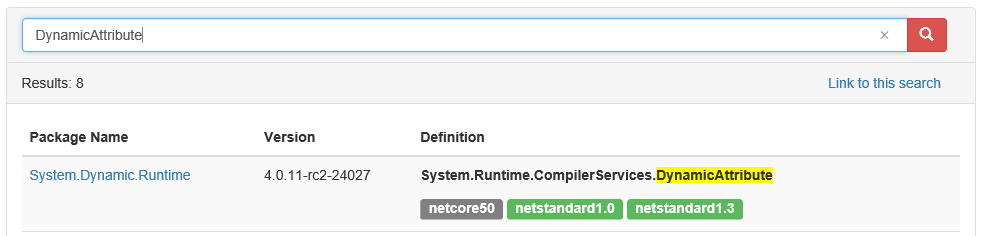

This is quite easy to resolve if this functionality has been ported to one of the many new .Net Core packages. The Reverse Package Search website is a great tool for finding NuGet packages that contain different types. For example, searching for the missing DynamicAttribute from the above error returns the System.Dynamic.Runtime NuGet package. This just needs to be added to the list of dependencies under the netstandard node to resolve the missing reference exception.

GetTypeInfo

One of the most common issues is that a lot of the old System.Type reflection functionality has moved to TypeInfo in .Net Core, which you can access through the GetTypeInfo extension method on Type.

So, instead of

var members = obj.GetType().GetMembers();

you would now use:

using System.Reflection;

var members = obj.GetType().GetTypeInfo().GetMembers();

I am sure that more elegant solutions will come out in time, but for now the way I am handling these differences is with compiler directives. What I have found effective is to create a TypeExtensions class with extension methods on Type. There I replace the various Type properties with methods of the same name, with separate implementations of each method for each supported framework. This, at least, constrains the compiler directives to one place, rather than doing it for every method, and leaves the production code free of compiler directives.

#if NET40

public static class TypeExtensions

{

public static Assembly Assembly(this Type type)

{

return type.Assembly;

}

public static bool IsValueType(this Type type)

{

return type.IsValueType;

}

}

#else

using System.Linq;

public static class TypeExtensions

{

public static Assembly Assembly(this Type type)

{

return type.GetTypeInfo().Assembly;

}

public static bool IsValueType(this Type type)

{

return type.GetTypeInfo().IsValueType;

}

}

#endif

So, instead of calling the Reflection property, my code now calls my extension method with the same name. For example:

// type.IsValueType;

type.IsValueType();

Compiler directives or rewrite code

It is not ideal to have too many compiler directives in your code. When a feature you were using in the old framework has not been ported to .Net Core you have a choice to make

- Write a new solution for .Net Core and switch between the old and new implementations with compiler directives, or

- Replace the original implementation with a new one that works for both frameworks

For example, I had some JSON serialization functionality that relied on the JavaScriptSerializer in the System.Web library. This serializer has not been ported to .Net Core, so the short term fix - to get things working - was to use compiler directives to keep the existing soluiton for .Net 4 and provide a new solution for .Net Core.

#if NET40

using System.Web.Script.Serialization;

public class JsonSerializer : ISerializer

{

public string Serialize(object obj)

{

var serializer = new JavaScriptSerializer();

string json = serializer.Serialize(obj);

return new JsonFormatter(json).Format();

}

}

#else

using Newtonsoft.Json;

public class JsonSerializer : ISerializer

{

public string Serialize(object obj)

{

return JsonConvert.SerializeObject(obj, Formatting.Indented,

new JsonSerializerSettings

{

NullValueHandling = NullValueHandling.Ignore,

ReferenceLoopHandling = ReferenceLoopHandling.Ignore

});

}

}

#endif

As more things get ported to .Net Core though, ideally I would hope to remove compiler directives and have a single solution that works for both frameworks, because it really is not ideal to maintain multiple implementations of lots of functionality throughout a codebase.

Thankfully, the DataContractJsonSerializer has been ported to the System.Runtime.Serialization.Json NuGet package, so I can actually have a single solution that is supported by both frameworks and remove the compiler directives.

using System.Runtime.Serialization.Json;

public class JsonSerializer : ISerializer

{

public string Serialize(object obj)

{

var serializer = new DataContractJsonSerializer(obj.GetType());

string json;

using (var stream = new MemoryStream())

{

serializer.WriteObject(stream, obj);

json = Encoding.UTF8.GetString(stream.ToArray());

}

return new JsonFormatter(json).Format();

}

}

Why didn't I just use Json.Net or ServiceStack.Text to serialize Json? Well, I would if I was building an application, but for a NuGet library I don't want to add a NuGet dependency just for one class of functionality. That might be old world thinking though, given how much of the .Net Framework is now provided as NuGet packages. I may just change my thinking on that but, for now, I still see a distinction between third party packages and .Net packages.

Backwards-compatible Polyfills

Credit to Jake Ginnivan for this solution. It is actually pretty easy to satisfy the compiler by providing polyfills, or shims, for types that have not been ported to .Net Core.

For example, Serialization has not been ported, but you might have classes with the Serializable attribute on them. Providing an empty SerializableAttribute class in the System.Runtime.Serialization namespace will satisfy the compiler for your .Net Core code.

#if !NET40

namespace System.Runtime.Serialization

{

public class SerializableAttribute : Attribute

{

}

}

#endif

Another example I have come across is a polyfill for AppDomain.CurrentDomain, now that AppDomains are no longer supported in .Net Core.

private sealed class AppDomain

{

public static AppDomain CurrentDomain { get; private set; }

static AppDomain()

{

CurrentDomain = new AppDomain();

}

public List<Assembly> GetAssemblies()

{

... // .Net Core functionality here

}

}

Summary

There are a lot of exciting new things to learn with .Net Core. Porting your existing code to the framework is a little bit of work - but not too much. The process is quite straightforward with predictable steps, most of which I've hopefully communicated here. The .Net Portability Analyzer is a huge help in enabling you to plan out the conversion beforehand, providing you with a list of issues and - most helpfully - even the solutions to most of the issues. The main area of concern is to provide new solutions for areas of the code that rely on parts of the .Net Framework that have not been ported. Thankfully, this seems to be a reasonably small surface area though, of course, it will depend on each application.